Press

Art News I The Washington Times I Art in America I Arts Magazine I Dialogue I Museum and Arts I Arts Magazine I The Washington Times I Getler/Pall Newsletter I The Art Gallery Scene

New York Reviews

November 1985

Review by Gerritt Henry

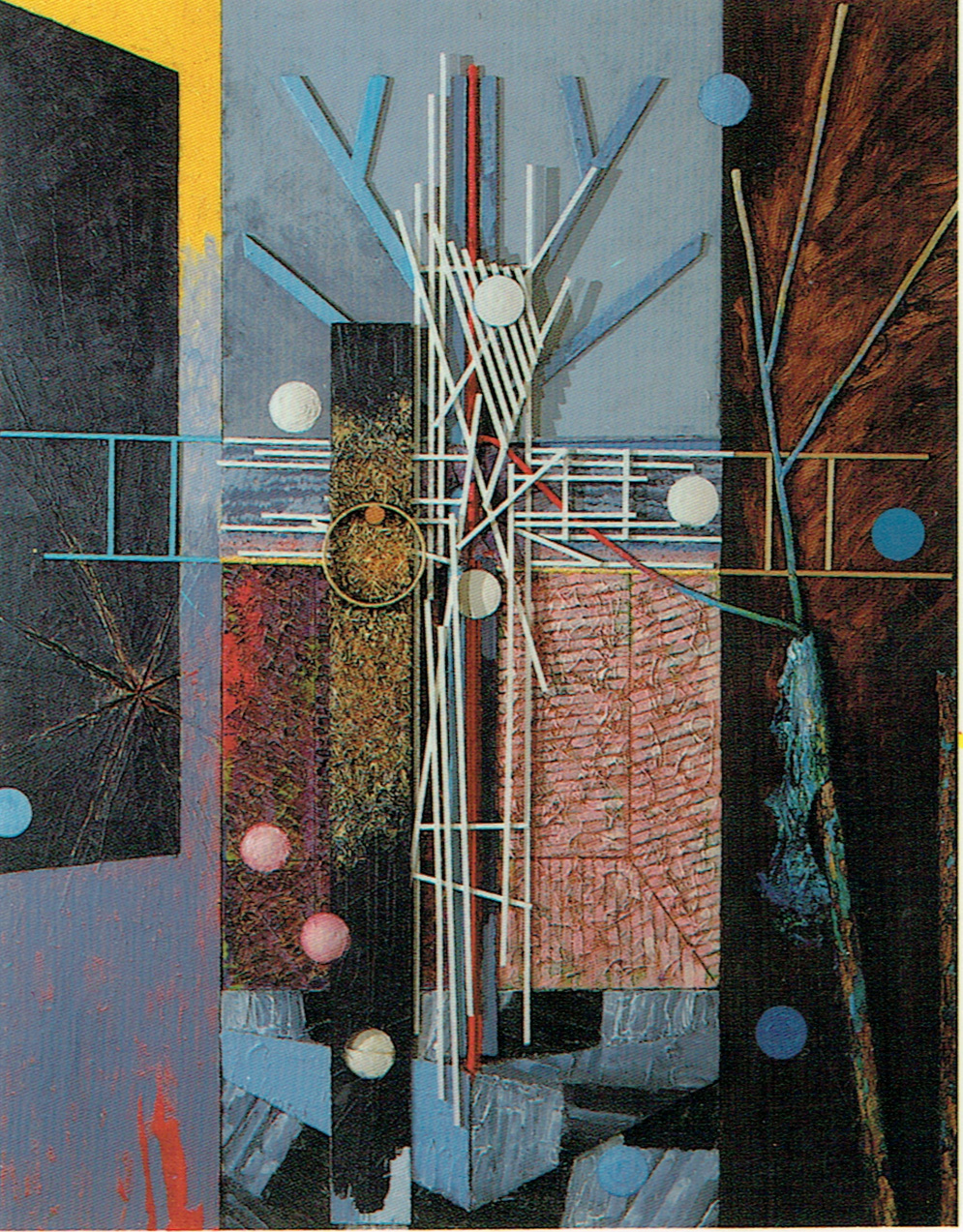

These new paintings and works on paper were built up with layers of acrylic and such disparate elements as wood, cloth, rope and hair. Shepherd's Gate (1984) was a typically complex example: Constructivism seems to be the key to the work, a two-dimensional structure of blue and white sticks, resembling a trellis here, a fence there. The sticks are dotted with painted circles, stripes, triangles and diamonds.. The work also has areas of thickly applied acrylic (with and without hair) in grid patterns. Along the top, a starburst form- one of Carboni's favorite motifs- seems to have been incised into the paint.

As with Constructivism, one is drawn to Carboni's work not so much by the imagery as by the dynamic formal energy. Vine (1985) is a five-part piece that includes his familiar stripes and circles, a red string on oxblood impasto, a small structure of blue and green sticks, a gold-and-white-painted area with holes cut into it, a purple scumbled ground with stripes in white and, finally, a starburst.

So complex are Carboni's works- so miniaturistic yet so vast in their devices- that one could spend pages describing each one. Suffice it to say that in Carboni's vision the modern is put to personal, idiosyncratic uses. Yet the peculiarities never make for obfuscation; they seem to be the articulation of a subconscious realm where esthetics and psychic processes meet and mingle. There's a lot of excitement in these works, but never at the expense of the highly developed painterly and collage-like qualities.

Getler/Pall/Saper Gallery, New York

Richard Carboni, Shepherd's Gate, 1984, mixed media, 60 x 48 x 3 inches. Getler/Pall/Saper

June 18, 1987

Review by Alice Thorson

Two years ago, critics who saw the writing on the wall for the revival of abstraction hailed New York artist Richard Carboni as a pioneer. Defying formalist canons of purity and reductivism, his accretive, alluring abstract reliefs signaled a change in the wind. It now blows full force.

Mr. Carboni's current show at Marsha Mateyka Gallery (2012 R St. NW) evinces his continued fascination with an architectural vocabulary of scaffolding, corridors, corners, arches - which he here mixes with cosmological references to stars, planets, eclipses.

Rich textures result from the artist's collage approach. In "Corridor (False Stars)" (1987) the largest and most excessive work on view, tiny relief globes float through a skewed scaffolding. Baroque passages of impasto, achieved by transferring globs and smears of pigment painted on waxed paper onto the surface of the work, join strips of cheesecloth, also affixed to the surface, and areas of paint mixed with hair.

That the effect of all this is highly decorative attests to the artist's considerable formal skill. But as always, through a careful balancing of image and allusion, Mr. Carboni manages to keep the work's formal flair firmly wedded to his conjuring of a mysterious netherworld of the imagination.

Perhaps in response to the AIDS benefit, perhaps because his small works have proven successful in the past with Washington buyers, this show was limited to modest-sized works on paper. The large paintings are even more enticing.

Marsha Mateyka Gallery, Washington D.C.

March 1983

Review by Tony Towle

At first glance, these 16 mixed-medium works on canvas or paper appear to be abstractions, with hints of the representational in color (a sky blue or a grass green, for example). In their use of painted, collaged sticks, they are sometimes almost totemic in feeling. The metaphorical aspect of the works is reinforced by the titles: Ascent, Well, Horizon, Sky etc. Sky (19 x 24") is fairly typical of the smaller pieces: in it a thin stick is suspended from string against a background of sky, a range of hills in taupe and a dark green squared "U" shape; the stick appears to be resting on the point of a black equilateral triangle.

Richard Carboni, Sky, 1982, mixed mediums on canvas,18-3/4 x 24 1/2 x 2 1/4 inches; at Getler/Pall

The metaphorical aspect of the works is reinforced by the titles: Ascent, Well, Horizon, Sky etc. Sky (19 x 24") is fairly typical of the smaller pieces: in it a thin stick is suspended from string against a background of sky, a range of hills in taupe and a dark green squared "U" shape; the stick appears to be resting on the point of a black equilateral triangle. What little "reality" there is in this scene is further lessened by the whitish-gray brushstrokes that make up a sort of curtain covering the upper half of the sky, and the groups of blue triangular shapes (black at the upper edge) collaged above it.

On examination, each of these triangular shapes is seen to be a painted and collages paper airplane. Carboni's most unusual device, these planes appear in most of these works, always in groups forming a larger pattern and in different colors. Perhaps they slightly signify the man-made, but oddly enough, although Carboni's work is not without humor, the planes are not at all funny - they have none of the feeling of the grade-school prank that one usually associates with them.

Other materials that Carboni usues in these works (in addition to paint, string and sticks) are sand, wood shavings, sawdust and hair. Painted but not disguised, they add to the atmosphere of personal symbolism that pervades the work. However, except for the blue and green, Carboni's color does not appear to be symbolic; it is chosen rather for its harmonious effect.

Symbolic possibilities aside, these "mixed medium works" are basically paintings, and Carboni's handling of paint is assured. The other elements are so neatly blended in that (except for the sticks) they are not even immediately apparent. Even the strings appear, from a short distance, to be painted lines.

The size of the works varies from 10 by 13 inches (Cage) to 44 by 32 (Antigravity [for Houdini]) and although the latter is successful, Carboni seems more at home here in the smaller scale. The smaller works are finally not so much abstractions as metaphoric distillations. One has the feeling of looking into some other, but vaguely familiar world.

Getler/Pall, New York

April 1983

Review by Janice C. Oresman

The paintings of Richard Carboni have a lyrical quality appropriate for an artist who is also a published poet. Barely thirty, Carboni has pursued his career unstintingly since his student days and in a very short time has found a highly responsive public.

Richard Carboni, Ghost (for Houdini), 1982. Mixed media on wood, 25 1/2 x 33 1/4". Courtesy Getler/Pall Gallery.

He started out as a figurative painter favoring oil on canvas. As he used color with more freedom he began to think about why he chose certain colors over others. This led to chromatic experiments and a gradual elimination of the figure except for phantom vestiges of the female form which appear from time to time. He carried out his investigations with paper rather than canvas and soon became intrigued with paper as a material. He began to create forms with collage, often folded into three-dimensional shapes, and that is his primary technique today. Because these collage elements are invariably covered with paint, he refers to his work as painting. A fascination with Tantric art encouraged him to simplify his art through the use of symbolic color and mystical signs in an effort to make it more "universal" in meaning.

By the time of his first exhibition of "Works on Paper" at Getler/Pall in 1980, his vocabulary had been established. Totem II, of that year, is a compendium of the style and imagery he had developed. The composition is organized with rectangles of color which all have meaning according to Tantric canons. As the "totem" is traditionally devoted to ancestor worship and preserving the spirit of the dead, so Carboni's totems preserve objects that are significant to him. Here the central area is composed of old letters, drawings of figures collages randomly, and human hair sealed in rhoplex. A layer of rich gold acrylic is used as a "skin of color" through which these various talismans are revealed. Symbolically and visually the effect is that of an icon. The spiritual connection is furthered by the inclusion of sticks which are painted white to resemble bones. They are found in many of his paintings and refer to trees or bodies that were once alive. Such sticks and bones are used in American Indian and African religious rites.

The use of Tantric symbols has enriched his narrative. Ghost (for Houdini) (1982), according to Carboni, was inspired by the famous magician who was the master of escape and knew all the tricks. He believed that he could even trick death and invented a code by which he was sure he could communicate with his wife after death. Houdini is represented by the specter-like stick inhabiting what Carboni calls the white "spiritual chamber." The futility of Houdini's ambition is indicated by the form itself, which is wedged between two wood panels and bound by lines and strings, as well as by the folded paper airplanes that are thwarted in an attempt to fly as they are secured to the surface with glue. Carboni always tries to achieve an equipose between the opposing forces of stasis and motion. In other paintings trapezes and kites imply motion but are held back by strings.

Houdini's frustration is soon forgotten in the face of the painting, with its dazzling color. Delicate patterns formed by lined paper and interlocking collage motifs are further enlivened by chevrons of color and strong intersecting lines. A decorative quality ensues which has nothing to do with any contemporary traditions of pattern or decoration, according to the artist, but is dictated by the structure of the work. The vitality of the surface, which is fresh and alive, belies the somber message of Houdini or the human condition it comments upon.

Carboni is devoted to handmade paper which he chooses for its beauty as well as its projection of human involvement. One especially appealing work in his last exhibition, Journey (1982), is supported on a tactile gray paper which provides a wide border for the iconic painting. The passages of folded paper and rich colors highlighted with gold appear to be displayed in a jewelry case. The beauty of origami as well as the spirit behind that technique is echoed in his work. Carboni's care for materials earned him one of the first awards offered last year by the Ariana Foundation for the Arts, an organization devoted to mixed media.

Carboni is animated and articulate about the meaning of his work. He prefers, however, to be judged by his art and not by the content which he considers to be simply the information from which the painting is shaped. The final result, regardless of reference, can be appreciated for its visual aspects and the extreme thoughtfulness with which it is conceived, as well as for his unique approach to contemporary non-representational art.

Getler/Pall, New York

Volume 9, Number 2

March/April 1986

Interview by Louis A. Zona

Director of the Butler Institute of American Art

Richard Carboni, Breath 1984, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 28 x 60" (3 panels). Photo courtesy Getler/Pall/Saper, New York.

LZ: I think of your work as a balance of formalism with an element of conceptualism - almost like constructivism meeting dadaism. Could you comment on this?

RC: I think it is closer to surrealism really, more like Max Ernst's style of semi-abstract surrealism.

LZ: Are you interested in formalism? The work seems well planned and carefully structured.

RC: It is very well planned out. I associate formalism with a kind of abstraction that I don't have much interest in - like color field painting. A lot of my work was influenced by tantric art (an Eastern religious art in which geometric forms are used to describe a philosophy of life and death). Each of the symbols represented a larger life issue. I used them and climbed back into being an abstract painter. I adapted a lot of their symbols and gradually this became a way of bridging personal ideas and more universal work. I started as a figurative artist (rooms, people, etc.) I then became frustrated and wanted to make it a more universal work. I felt that if i could combine them both, the figurative elements with an overlay of abstract forms, that the best of both worlds would be available. So they became superimposed. The work for the most part appeared abstract with vestiges of figures and other identifiable objects just barely visible beneath the surface. Color for me was, at the time, too arbitrary so I adopted a lot of their color principles and the work became black, gray, red and white. At a time when most artists were going to more figurative work, I wanted something more ambiguous and abstract.

LZ: In a formally constructed work like Breath (1984) one detects as well an element of symbolism. What were you after?

RC: Breath is a triptych. The center panel represents the world. In the right hand panel the human element is magnified with its flesh color. The black spots from the constellation Pegasus, a symbol of both escape and freedom yet, because of its fixed position in the sky, it becomes a symbol of man's frustration at his inability to escape. The left panel represents a world beyond this one with all its possibilities. Each element was formally worked out.

LZ: Shepherd's Gate is rich in surface texture and people writing about your work are amazed by the surfaces. Would you care to comment on that?

RC: Actually, within one painting there are a lot of approaches. Wood shavings and human hair depict the human sphere. There is a flatter side to the painting which is the black and gray area - the emptiness and nothingness part of the painting. Where there is the human, there is a lot of texture.

LZ: In terms of preliminary drawings, do you carry them to a finished quality?

RC: The preliminary drawings are just sketchbook drawings. No worked up drawings are done because, if I get involved in that, I wouldn't have to get into the painting. They would be finished works in themselves.

LZ: Where do you see the work going?

RC: I like where they are now. There is a balance between abstraction and realistic forms and that gives me great room to play in. it makes it much more exciting to have both. I can see parts of the world, things that supposedly make up parts of the world like seas, mountains, rooms etc. and in between I see spaces as well. In these paintings I can make arrangements of these parts and hope that the whole is sensible and believable in its attempt to describe the world. That's how I make sense of the world. Or, as Eleanor Heartney said in a recent article about my work, its a groping for meaning. I'm not interested in painting figuratively nor in pure formal painting, which leaves me balancing on a high wire where I can play and take from both worlds and create something.

Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio.

Review by Florence Gilbard

Carboni's Faith

January/February 1989

Richard Carboni, Blue Heart, 1988, Acrylic and mixed media on wood-relief.

Around the corner at Marsha Mateyka on R Street, Richard Carboni's flamboyant constructions burst forth like the fulfillment of that promise. In the artist's own words, "The forms blossom and you'll notice the predominance of circles and balls. These i think of as cells or spores, always full of potential."

Carboni's wood panels are assembled with paint, string, sticks, hair, wood shavings and cloth. There's an obvious affinity with the more whimsical Surrealists- Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Hans Arp and Joseph Cornell.

Carboni is a New Yorker whose poetic sensibility pits him in an uncomfortable struggle against the devils of Manhattan's art scene cynicism. It's evident in his art's edgy tension between lyricism and crudeness. "Ultimately, my work is an attempt at finding a system of belief, a faith, but I always end up feeling that painting is unable to give or restore faith."

Carboni's abstractions never stray far from the natural world.The forms are organically derived, inspired by plant life like much of the Surrealist's work. The intriguing surface textures and rich though gentle palette try to seduce the eye away from the more provocative revelations of the constructed underpinnings of the image. "The raw wood and holes punched in the organic forms undermine what appears, at first sight, to be a grappling with 'big issues,' but this exposure mocks that stance. I'm always asking, 'How much can you really say?'"

At first Carboni's work draws you across the room because, like spring, it's so pretty - those dreamy colors, the textural refinements and whimsical formalities-but it's the structural complexity, that rawness Carboni won't hide, that keeps you looking up close.

Marsha Mateyka Gallery

May 1985

Review by Eleanor Heartney

Haunted by the irreducibility of art to life, Wallace Stevens declared, "The ultimate poem is abstract." Now, after a period of eclipse, abstraction is creeping back into the art world in group shows at galleries and museums, in the lionization of established and newly emerged abstract artists, in an impatience with the assumption that the presence of the figure in itself is enough to ensure substantive content.

Rope Trick (Span), 1984, Acrylic & mixed media on wood, 16 3/4 x 24 3/4" Courtesy Getler/Pall/Saper Gallery

The new (or rather, the newly visible) abstract art shares with the prevailing figuration a rejection of formalism's narrow concerns. At the same time, however, it implies a discomfort with the allegorical impulse that pervades so much recent figurative art. Thus abstraction today must grapple with the problem of creating meaning which goes beyond formalism but stops short of symbolism.

Richard Carboni's constructed paintings walk this line between reduction and metaphor. As his works have developed over the last few years from a reliance on tantric symbolism as a code for meaning to an art that dances on the edges of representation, he has struggled with the question of how much and how little a work of art should say. For some time he has been interested in an art of disjuncture. His works have tended to be pieced together of panels of wood or paper to which he attaches three-dimensional objects, bits of string, wooden sticks, hair or wood shavings mixed with paint, even small, folded paper airplanes arrayed in evocative combinations that suggest landscape or interiors without really describing them.

Many of the works are long and horizontal, demanding to be read like Japanese scrolls as a succession of related but not necessarily continuous images. This format was inspired from a line from a John Ashbery poem: "It is the old sewer of our resources / disguised again as a corridor," which to Carboni signifies the all-too-human tendency to sweeten the banal facts of existence with the illusion of significance or purpose. The corridor image allows Carboni to take an object or idea through a series of transformations, as in Vine Piece in which the tendril of the title moves through a series of representations from abstracted blossom to building scaffolding to an internal circulation system to a recapitualtion of all of these. Other corridor pieces offer what Carboni thinks of as a series of rooms, juxtaposing internal and exterior realities in the form of partially suggested interiors, landscapes and night skies.

Carboni's symbols remain deliberately schematic: a grid of slightly raised rectangles textured with hair or wood shavings becomes a brick wall, perhaps the space of the artist's studio, while a patch of black or dark blue sprinkled with white dots refers to the night sky. Sticks laid in parallel lines become a ladder; shooting off from a central core they suggest a tree; laid at right angles they form a cross. The latter configuration appear in Shepherd's Gate which the artist notes is about both spirituality and its elusiveness in a material world.

A small work entitled Rope Trick (Span) reveals another kind of ambivalence. It contains a flat trapezoid suggesting a window in perspective, a wedge of dot sprinkled night sky, a jumble of triangular wood chips painted sky blue and forest green, and a plane of the hair-strewn brick wall. Arrayed side by side, these elements suggest an inventory of the universe whose separate parts are arbitrarily and almost forcibly united by a long wooden stick attached to wooden blocks on either side of the work.

In some of Carboni's recent works the space has become more unified; instead of a series of vignettes, we catch glimpses of a single space. Hints of illusionism have been creeping in (windows, horizon lines, ceilings, and corners meeting in the near distance). But even in these works, ambivalence remains a key element. The applied objects break the illusory surface as do holes occasionally bored through the wood backing; despite their roles in the overall composition, they remain sufficiently untransformed to break the spell of unity. Rope Trick (Growth), for instance, presents an interior space with walls, floor, and starry sky for ceiling. The promise of order made by this illusionistic space and by the triangular piece of wood set squarely in the middle is denied by the proliferation of other objects scattered across the surface: a green vine-like growth of sticks, a white plastic circle, a pair of blocks linked by a strip of wood. Again, the expected harmony is not achieved.

Carboni takes as an exemplar the great magician Houdini who devoted his life to the exposure of fraud among spiritualists and mediums, not out of disbelief but from a sincerer longing to make genuine contact with the spirit world. Carboni's work is like that; it is a tentative groping toward meaning and belief which longs to be satisfied yet is fully aware of the pitfalls in its path. His is an abstraction that is as keenly aware of absences as of presences and, like the winter spectator in the Wallace Stevens poem, beholds both "nothing that is not there and the nothing that is."

Getler/Pall/Saper Gallery

Thursday, February 23, 1989

Review by Alice Thorson

"Passage," 1988, mixed-media wood relief

New York artist Richard Carboni heats up the interaction between geometric and organic forms in his series of dynamic mixed-media wood reliefs on view at Marsha Mateyka Gallery (2012 R St. NW) through Feb. 25.

These new works are more dimensional and assertive than the works on paper of his last show at Mateyka. Colorfully painted and roughly textured with modeling paste and Rhoplex, the relief elements appear to burst from their flat pine frames - as if the artist had dynamited the picture plane.

Deep ruptures and channels. teeming spheres, and a preponderance of furled forms enhance the sense that what we see is the result of an excavation. a digging and uncovering both formal and symbolic.

Manipulating this set vocabulary of elements, Mr. Carboni explores the universe from different vantage points. There is a geological feel to "Plot", where a rent in the burbling surface offers what might be a view into the earth. "Greenland," on the other hand, presents a more topographical interpretation: planetary disks mill over a blue, green and white painted surface suggestive of water, land masses and arctic regions.

In the artist's mind, the circles and spheres which provide a formal constant throughout these works represent "cells or spores, always full of potential." But if he celebrates the drive toward multiplication, Mr. Carboni simultaneously countenances the explosive interaction of opposites that brings the new into existence. His mission is discovery, philosophical as well as artistic.

Richard Carboni

by Jeffrey Rian

From October 19 through November 20 we will be showing recent work by Richard Carboni, who will be having his second one man exhibition at Getler/Pall. Carboni works in collage, on paper and canvas. Starting with a visual or symbolic referent, he builds the work additively using a palette of specific elements that reappear throughout his work, including folded paper airplanes, cut paper, hair, sticks, wood shavings and ruled paper. These constituent elements are linked by extension to the title, expanding the metaphor both internally and externally through poetic association. In the majority of his pieces he incorporates a schematic diagram of a room, or a rectangular open shape. This is the only internally spatial reference in his work. In certain instances the airplanes inhabit or hover around this abstract space, pointing to a direction in the works themselves. However, as paper airplanes are manifestly directionless, and rely on chance to hit their target, their implication is, by way of their artistic intention, not pointed, but ephemeral.

In Trapeze IV, the formal construction is based on a square which has been cut in at the sides and slightly extended at the top and bottom. Inside a dark outer square is superimposed a linear diagram of a room. This room is further bifurcated by a black rectangle over which is suspended a collaged trapeze made of stick and string.In the center of the piece, on the black, is a white dot which is situated above an isosceles triangle. The dot provides a focus for the piece around which all of the elements have the illusion of balance. The trapeze, hanging over the black triangle, functions as a metaphor for mutability (with which the trapeze artist is in perpetual flirtation). It is, simply, that order is an illusion around which is constructed an impression of balance. This point of illusionistic repose, optically alluded to in Trapeze IV, is precisely where the artist situates himself; and,like the trapeze artist, he attempts to defy death and artistic failure with the continual shifting and restructuring of the facade.

Color and symbol are employed in a manner similar to that in Tantric are where repeated motifs appear in work after work as universal symbols. Carboni corrupts tantric associations with his own system of signs that are more in tune with western eyes. This system relates rooms to an internal world, paper airplanes to ephemerality, hair to personal/artisanal connections, line to internal form and overall shape to either open or close the work.

Color, for the most part, is primary, straight thalo blue or green, orange, red string, gold paint. Like the structural motifs, color is utilized first metonymically and then as a purely visual component.

In Short River a central image divides the picture plane into symmetrical halves. The title refers to a central rivulet (of blood) where the body of the work is split open and held apart by red string which is attached to each side of the work. Taking the metaphor a bit further, attached to the string, on each side of the rivulet, are four sticks of equal size, painted white, which are the ribs of the piece.

As in Trapeze IV, a schematic room centrally divides the picture plane. At the extremities of the rectangle are bilaterally symmetrical hemispheres composed of folded paper airplanes fitted together and fanned out to the corners. At the extreme edges the fans fade from black into blue one one side and black into orange (the complement of blue) on the other.

New York

Carboni at Getler/Pall

1982

Review by Jon Meyer

Richard Carboni's Short River collage/mixed media, 1982

With all the attention received by the return to the figure and new image painting, it is easy to forget that standby of modernism - collage/mixed media. Art as a problem to solve, surface as texture, color fields, and color studies are not quite dead. Richard Carboni takes these well-worn techniques in his own direction at Getler/Pall. His neatly framed, calculated but understandable spaces are arenas for the push and pull of the color theory to be tested again. Solutions to the classical problems of Albers and Itten are mixed with mathematical proportion, incised geometry, and angular linearity. Playful paper wings contrast with the vibrato of short, painted sticks, strung on string.

In a number of Carboni's works, Goethe's triangle appears to balance stationary stick trapezes and black wood strips. Cut out circle chords and arcs are dropped onto some of the works and painted with progressive value and hue shifts. Grids also appear. Most of the art applies the convention of blue on top, green and black on the bottom.

Short River contains two half mandala-like cobwebs with Jasper Johns chevron dabs. The structure fades yellow to black on one side and blue to black on the other. Red string emanates and ties meaningless knots around reiterated short painted sticks. Light tension on the string pulls open paper labia, a la Judy Chicago, revealing blood red overlapping brush strokes.

Journey uses a familiar format, a handcast grey paper square frames a sampler of stylized elements from other pieces. One rectangle is colored etching ground brown. Hair strands are embedded in the paint and more white dab chevrons appear. Blue lined white notebook paper sheets are formed into wings that are colored gold, red and blue.

Like many of his predecessor collagists, Carboni's work borrows geometric, Tantric symbology, and injects this into divisive, textured, brightly colored fields mixed with patterns. The result is elegant and tasteful - old guard avante guard - or perhaps neo-modern.